Above: Daniel Barenboim, the Staatskapelle Berin, Wolfram Brandi on violin and Yulia Devneka on viola play Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra, K364.

Above: Daniel Barenboim, the Staatskapelle Berin, Wolfram Brandi on violin and Yulia Devneka on viola play Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra, K364.

25 May — No sharing the spotlight with my dad for your coincidental birthdays this year, John my bonny. And as promised in my posting three weeks ago, “A Sexy NYC Memory to Celebrate the 3rd Anniversary of Falling in Love with Conductor John Wilson; Plus the BBCSO Doing Elgar’s Bach Fantasia; and Theatre of Blood (United Artists, 1973) Complete”, here’s that Britten piece.

Ed Lyon tenor, Benjamin Appl baritone, and Susanne Bernhard soprano are the soloists. The Choir of Hanover and the Liverpool Cathedral Choir round out the voices. Orchestra is the NDR Radiophilharmonie, Andrew Manze is the conductor. 2018. Above: War Requiem, written in 1962 by Benjamin Britten.

Ed Lyon tenor, Benjamin Appl baritone, and Susanne Bernhard soprano are the soloists. The Choir of Hanover and the Liverpool Cathedral Choir round out the voices. Orchestra is the NDR Radiophilharmonie, Andrew Manze is the conductor. 2018. Above: War Requiem, written in 1962 by Benjamin Britten.

I sang in the chorus of War Requiem around the time you were going on 1. It was the last concert of the Minnesota Orchestra’s ’72-73 season in Minneapolis; guest conductor was Kurt Adler of the Metropolitan Opera. (Don’t remember the soloists.) It was the greatest musical experience of my life. I know the Decca recording is out there somewhere, but the broadcast above from Radio Hanover is the closest I’ve found to the feeling I got being in the middle of all that gorgeous sound…

Which brings me to address yet another one of those sundry feelings I have about you, and have had about you, lo these several years: besides tenderness, gratitude, annoyance, and raging lust, just a trace of envy that you ascend to such an exquisite sonic plane so often…

But the envy goes when you bring it on home to us, which you always do. And then I’m filled with the pure joy of loving you.

In an earlier posting (“A Sexy NYC Memory to Celebrate the 3rd Anniversary of Falling in Love with Conductor John Wilson; Plus the BBCSO Doing Elgar’s Bach Fantasia; and Theatre of Blood, United Artists, 1973”) I mentioned TofB, which came out the summer I moved to Greenwich Village. Recently I discovered a new bio of Vincent Price entitled Vincent Price: The British Connection (Telos, 2020) where, to my delight, Gateshead-based author Mark Iveson reveals the torrid affair between Price and the noted Australian-born actress, Coral Browne:

Above Diana Rigg, Coral Browne and Vincent Price: Michael J Lewis’s excellent, elegant opening music for Theatre of Blood. Full movie here.

Above Diana Rigg, Coral Browne and Vincent Price: Michael J Lewis’s excellent, elegant opening music for Theatre of Blood. Full movie here.

Price’s infatuation intensified, regarding Coral as “the Great Barrier Reef—beautiful, exotic and dangerous. I was like a bird dog!”

“I remember he electrocuted me on my birthday,” Browne recalled when she performed her death scene with Price. Ironically her acting isn’t very good in this scene because she doesn’t look even remotely terrified of her murderer. Instead, she prefers gazing into his eyes instead of screaming in fear.

After the day’s filming, Price once again approached Diana Rigg for advice. “I said to Diana, ‘I understand it’s Ms Browne’s birthday. What could I get her?’ And Diana said, ‘Well, you know what she wants. You!”

And from then on,” added Rigg, “they never looked back. I think they fell into bed and I think it was a wildly sexual relationship. Incredibly sexual. I remember Coral saying that they worked out their combined ages were 120-something, and when you saw these absolutely shagged out people on the set, it was really quite funny. And that was the start of it.”

There are 3 naked ladies in this blog. This is one of them.

“I’m not given to displays of emotion, but when Maria and I met up again [to record the R&H album] we had tears in our eyes. She’s so exotic!” enthused my bonny conductor about this Detroit-born soprano. “I love her—as a person!” Yes, John. I’d love to hear more.

Above proudly nude Salome in the 1991 Covent Garden production of Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera directed by Ewing’s husband at the time, Sir Peter Hall: “Bali Ha’i” sung by soprano Maria Ewing in the compilation Rodgers & Hammerstein At the Movies, with The John Wilson Orchestra, conducted by John Wilson (Warners, 2011).

Above proudly nude Salome in the 1991 Covent Garden production of Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera directed by Ewing’s husband at the time, Sir Peter Hall: “Bali Ha’i” sung by soprano Maria Ewing in the compilation Rodgers & Hammerstein At the Movies, with The John Wilson Orchestra, conducted by John Wilson (Warners, 2011).

About the DVD recording of Salome, says Toronto blogger John Gilks in Opera Ramblings: “The production is really pretty conventional… Almost all the visual interest revolves around Ewing’s Salome though Michael Devlin’s scantily clad and palely made up Jochanaan is quite arresting too. Narraboth (Robin Legate) is an unremarkable actor and Herod (Kenneth Riegel) and Herodias (Gillian Knight) look uncomfortably like a couple of drag queens… The recording, directed by Derek Bailey, is about what one would expect from a 1992 BBC TV broadcast… This is probably worth having a look at as a record of an iconic performance by Ewing but I can’t imagine anyone would choose it as the definitive Salome.”

Here’s another exotic nude, just for my beloved John Wilson.

And the third and best, which you can find in the posting, “Cantara Christopher in Sadie (Bob Chinn director, Mitam Productions, 1980) as Indexed in the Database of the British Film Institute; and ‘Pictures of Lily’ by Pete Townshend”.

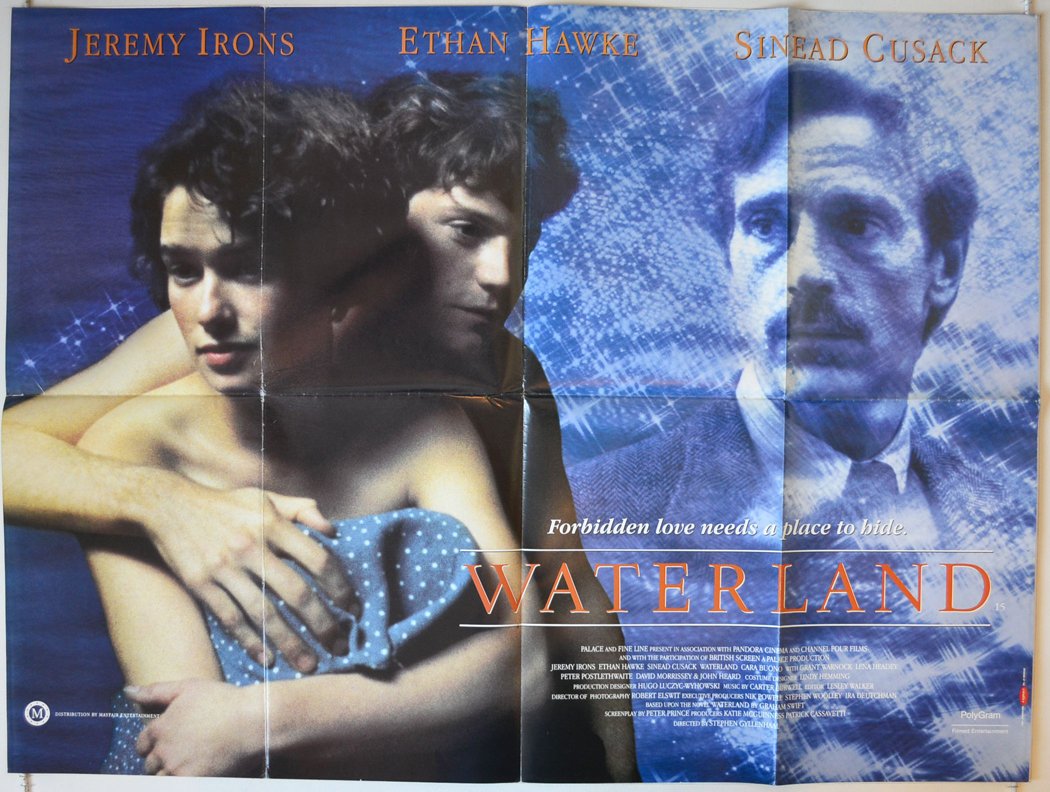

This is Stephen’s best movie, hands down. Whenever I think of Stephen and thinking of him raises my blood pressure remembering all the shenanigans he pulled on me, I also think of Waterland and (almost) all is forgiven between us, as far as I’m concerned.

That’s Lena Headey in her first screen role. Above Lena, Grant Warnock and Jeremy Irons: Carter Burwell’s gorgeous, haunting music from Waterland.

That’s Lena Headey in her first screen role. Above Lena, Grant Warnock and Jeremy Irons: Carter Burwell’s gorgeous, haunting music from Waterland.

I’m not a huge fan of Graham Swift‘s books, but I read his Waterland and Last Orders, and much prefer Last Orders as a novel but Waterland as a film, no matter how many trivial changes the screenwriter made. In Swift’s memoir there’s the amusing revelation that Steve got this assignment because although he was last on the list he was the only one available…yeah, that’s the Gyllenhaal Luck. Fortunately—really fortunately—Steve had with him a very good Director of Photography, Robert Elswit, and score composer Carter Burwell, whose music you can hear above.

I mentioned in another posting about his film work that “there’s a creepy, dreamy, nasty edge in almost all the sex scenes in Steve’s movies…” which certainly figures here. Not in the actual sex scenes between the teenage lovers, which are all lyrically rendered, but in that damn ABORTION SCENE in the woods, which never fails to get gasps from us females in the audience. Check it out. There’s a weird fairy-tale quality to this scene which is beautiful, but sooo the wrong tone.

Before we get to what I think will be a nice and fair assessment of John Wilson’s 2020 recording, a word to some people.

I have always been aware of the tacit agreement that exists between my screen persona Simona Wing and her fans, but let me now take this opportunity to state my position clearly: You all have my blessing to do whatever you want with me in your fantasies.

Because whatever you want to do with me in your fantasies is nothing compared to what I want to do with John Wilson in mine. So, go for it.

Now on to Korngold.

I didn’t realize this was still a thing in the music world, but apparently opinions continue to be strongly divided as to whether Erich Wolfgang Korngold—a true heir, by the way, to The Great Mittel European Romantic Tradition—deserves inclusion in the canon some snooty farts call the Classic Repertoire. When you mention the name Korngold, even the most knowledgeable music lover’s first thought is of upmarket movie soundtracks (Anthony Adverse—The Adventures of Robin Hood—The Sea Hawk—Captain Blood) and likely never gets around to the fact that Korngold wrote, among other things, the most luscious symbolist opera of the 20th century, Die Tote Stadt, in 1920, and a hell of a gorgeous violin concerto 25 years later:

(Click here to subscribe to the RTE Concert Orchestra channel and support them.)

So it seems like every generation there has to be one nut who comes along and says, Let’s run Korngold past the hoi-polloi again and see if he’ll fly—and if you think I’m talking about you, John Wilson, you’ve got a swelled head. Because the nut I’m talking about is the nut in the CIA. The anonymous nut who got The Company to fund an enterprise back in the early 70s called “The Golden Age of Hollywood Music” and hence to elevate Korngold to the status of Hollywood Royalty—but through his film scores and his film scores only.

But that story later.

We’re here right now not just to size up a new Korngold recording, but to honor the decades-long musical relationship of Andrew Haveron, violinist, former Leader of The John Wilson Orchestra, current Leader of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and conductor John Wilson, whose career in orchestra building started at the age of 22 and hasn’t stopped since.

Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D, their latest Chandos release, was going to get my attention with or without the Winsome Lad of Low Fell anyway, as I’m a sucker for this particular style and era of music. But I was glad to learn about their actual friendship as well; for me it explains why the perfect communication that’s so evident here between Haveron and my John (and through him, to the estimable RTE Orchestra) has some of the magic of Barenboim+du Pré, back in the brief days when those two were cooking hot with Elgar.

This is soloist Haveron’s star turn: a warm, fresh, intimate—revelatory even—rendition of a piece that, let’s face it, is kind of like the “Nessun Dorma” of violin concertos. But this is John’s success too. So much of my bonny’s gift for conducting Korngold, as we know, has to do with his insistence on a technique his PR people call “shimmer” but is actually wrist vibrato on strings, a technique in fingering I learned about and taught myself when I was 14 because I liked the sound it made, although when the orchestra teacher put it down for sounding cheap and sloppy I quit it.

But I know the sound of shimmer and you do too. The John Wilson Orchestra practically patented it. John himself still calls for it whenever he conducts Tchaikovsky. It’s in all the high-toned movies of the 1930s. It’s also in Rouben Mamoulian’s classic film musical Love Me Tonight (complete film here) courtesy of Paramount’s musical director Nat Finston, who understood what he was talking about when, in a certain musical scene, he said he wanted “crying violins”. I could tell what he was talking about when Mamoulian told me this story 46 years later.

NOTES for Korngold: Concerto & Sextet (Chandos, 2020) can be found here

NOTES for Korngold: Concerto & Sextet (Chandos, 2020) can be found here

A new production of The Turn of the Screw from Opera Glassworks, conducted by John Wilson at London’s Wilton’s Music Hall, was three days from opening in March 2020 when the first lockdown hit.

Director Selina Cadell and producer Eliza Thompson managed to rebook the cast of six singers and 13 musicians (from John’s own orchestra, the Sinfonia of London) for a run in October. But as weeks of lockdown turned into months, it looked like the project would be scuppered.

At which point, they rethought it for film.

The stage director and producer took the opportunity to experiment. “We weren’t interested in live capture,” says Thompson. “But we didn’t want the fact that it was intended to be a stage production to be lost.”

This influenced not just their approach with singers and a working method with camera director Dominic Best across the 6-day shoot, but also with the individual players forming John Wilson’s orchestra.

With the perfectly captured, decayed grandeur of its main, high-vaulted space dating back to 1859, the thrillingly atmospheric, Victorian-era Wilton’s Music Hall translates perfectly into the chilly, remote country house and garden in which the ghostly actions occur. Designer Tom Piper seized the opportunity to make the entire building a film set.

“Covid restrictions meant we couldn’t have all the musicians there together,” says Thompson. “So with the auditorium completely filled, becoming a Suffolk reed bed, we’ve planted the musicians throughout the film. As the story progresses, it becomes more anarchic.”

Cadell and Thompson have capitalised on the opera’s unique construction, individual scenes interspersed with an instrumental theme and 15 variations, to enhance the work’s filmic, non-linear nature.

The performance, still in the edit prior to being distributed via arts channel Marquee TV, is an equally impressive advance born out of Covid necessity. The vocals were filmed live, with the singers using microphones but without the orchestra. Instead, using monitors, John Wilson conducted them against live keyboards. Once the singers’ tracks were laid down, the orchestra was recorded to fit the singers’ interpretations, which is how it should be. ~David Benedict, from The Stage, 20 Nov 2020

*Catch a glimpse of the man I love on the monitor at 00:33 or here at rehearsal.

When I was back in grad school, I did a paper on the novella this opera is based on, The Turn of the Screw, my take being that the whole thrust of the story had to do with, at its core, author Henry James’s weird revulsion to/fear of sexuality—any sexuality—gay, straight, bi, kinky, whatever… Which in my ignorant prejudice I took to be typical of all English men anytime, anywhere—until I remembered that James was born not just American but, like my son, a native New Yorker (used to take The Kid to the playground in Washington Square near James’s old house) and he turned out fine. So it was fascinating to hear and watch OperaGlass Works‘s no-emotional-holds-barred production with my brilliant, bonny conductor John Wilson at the musical helm. Above Opera GlassWorks’s filmed production at Wilton’s Music Hall (2020): Britten’s 1954 The Turn of the Screw, with a superior libretto by poet Myfanwy Piper. Singers: Jennifer Vyvyan, Peter Pears, Arda Mandikian, Joan Cross, Olive Dyer, and as the young and beautiful boy Miles, David Hemmings! The English Opera Group was conducted by the composer.

When I was back in grad school, I did a paper on the novella this opera is based on, The Turn of the Screw, my take being that the whole thrust of the story had to do with, at its core, author Henry James’s weird revulsion to/fear of sexuality—any sexuality—gay, straight, bi, kinky, whatever… Which in my ignorant prejudice I took to be typical of all English men anytime, anywhere—until I remembered that James was born not just American but, like my son, a native New Yorker (used to take The Kid to the playground in Washington Square near James’s old house) and he turned out fine. So it was fascinating to hear and watch OperaGlass Works‘s no-emotional-holds-barred production with my brilliant, bonny conductor John Wilson at the musical helm. Above Opera GlassWorks’s filmed production at Wilton’s Music Hall (2020): Britten’s 1954 The Turn of the Screw, with a superior libretto by poet Myfanwy Piper. Singers: Jennifer Vyvyan, Peter Pears, Arda Mandikian, Joan Cross, Olive Dyer, and as the young and beautiful boy Miles, David Hemmings! The English Opera Group was conducted by the composer.

We all need a visit from the Empress of Delight every so often. So—here she is in all her youthful splendor, about to be kissed by handsome Jon Cypher.

Above Dame Julie and her Prince Charming: The entire audio of R+H’s 1957 original TV musical, Cinderella.

Above Dame Julie and her Prince Charming: The entire audio of R+H’s 1957 original TV musical, Cinderella.

I had a dream about you a few days ago, dear. It was very short. You were maybe 17, 18… You were standing on Tyne Bridge looking down at the river… It was a cool glassy day and the river was cool and glassy… And you were standing there, thinking and pondering that this was the finest sight there ever was… Then you turned your gaze eastward, toward the North Sea… But all you could see was a shimmery horizon, and maybe it was the sea, but it was calm as well and it made you think about how infinite and endless it was (you were only 17, after all)… And then after a few more seconds of pondering you turned to look at me and you said, ‘And that’s when I decided to love Vaughan Williams.’

A Sea Symphony by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the 2013 BBC Proms is available on YT here

Happy Valentine’s Day, John dear.

Above the sea, the sea Sakari Oramo conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the BBC Chorus, the BBC Youth Choir, and soloists Sally Matthews and Roderick Williams in Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No.1.

Another doddle for the weekend. Mason’s book, The Cats In Our Lives, which he wrote and illustrated, was open on display on my boss Mamoulian‘s library lectern the day I started to work for him.

That snooty critic fart Andrew Sarris once mock-praised my old boss Rouben Mamoulian for his early cinema innovations that never quite caught on. Hah! When’s the last time you were so proud of your old boss’s work you wanted to make sure the world never forgot it? So—here’s the most audacious musical film sequence ever directed, which magically links up the movie’s two singing stars Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald:

Above the lovebirds: Ella Fitzgerald sings this Richard Rodgers+Lorenz Hart perennial, which was scaled down from its operetta length for inclusion in The Great American Songbook.

Above the lovebirds: Ella Fitzgerald sings this Richard Rodgers+Lorenz Hart perennial, which was scaled down from its operetta length for inclusion in The Great American Songbook.

And if you’re still in doubt about Mamoulian’s genius, check out this opening scene which I uploaded especially for my bonny John Wilson for the beat:

“City Wakes”

from Love Me Tonight

Rouben Mamoulian, director

Nat Finston, music director-arranger

If I had seen Love Me Tonight before I went to work for The Old Man I would’ve been more patient with him. But I was only 23.

The entire film Love Me Tonight is available on my YT channel here

Happy 2021, my darling Low Fell Lad Made Good. I just tried getting on your management’s website for you (johnwilsonconductordotcom) to check for your January gigs when I was sent to the sinister Your connection is not private page, which perturbs me a bit as it sounds like the server might’ve been hacked.

[Sorry, have to go be with Mister Grumble for a while. More later, promise.]

[2 Jan 2021 14:20] Later. I’m back, dear. Glad to see that fixed, for now. Mister Grumble and I had a date to listen to what I just found on YT: the 1978 NYE Grateful Dead concert from The Closing of Winterland—you know, the one where [legendary band manager] Bill Graham glides down to the stage on a giant lit joint (as I described it to my blind angel which he recognized at once)—and really, it was a great night, or so the Mister tells me. The Mister is the one who turned me on to The Dead, back at our old commune in San Francisco.

But here I go rambling on about American things when I’m sure what you really want to hear is how you made out in 2020. Well honey, as you know, you did fine with your recordings on the Chandos label: Your 2 Korngolds, the symphony and the violin concerto, your Respighi, and the French dudes. I’m sorry you couldn’t conduct Tchaikovsky in Chile (sharing the same time zone with you would have been pretty cosmic), but you did “save” The Turn of the Screw at Wilton’s Music Hall, and that’s très chic.

Here is what I took away from you in 2020 (besides that perfect screenshot and your gracing me with your attention on St Crispin’s Day and the aforementioned recordings):

And speaking of the Proms, pardon me, my love, while I do some Fan Service for your fans :

[making dinner now, Bavarian-style pork chops with sauerkraut and boiled potatoes; I’ll come back to wrap this up as soon as I can, promise]

[6 Jan 2021 14:21] Okay, now that I’ve served all your wonderful fans around the world, let me have my say.

The BBC Proms 2017 semi-staged production of Oklahoma! pissed off 3 people I care about even though one of them is dead: Mister Grumble, a proud Oklahoman, who hated to see this nuanced Sooner tale turn into some weird English panto; original 1943 director Rouben Mamoulian, who even though dead howled in his grave at your dismissive use of his name in promos, oh, and for perpetuating a “mistruth” about him and his artistic relationship with Agnes de Mille; and me for two things: one, your use of the Robert Russell Bennett orchestration (which was never meant to play to a room the size of the Albert) instead of the film orchestration (by Bennett+Courage+Sendry+Deutsch) which, if I remember rightly, you actually used in your 2010 show for the last number, “Oklahoma!”, and it was gorgeous; and two—Marcus Brigstocke as Ali Hakim!!!??? Who the hell at the BBC was responsible for that whitewashing? And why didn’t the UK press call the Beeb on it? (I mean, if you’re all going to be hoity-toity over Maria in West Side Story…) Now, I can lay the former at your door but maybe not the latter, as the Beeb seems to have gone off its rocker on its own… But c’mon.

But let that pass. What really impresses me about my lust for you is that it started me on the road to thinking about The Old Man again. And actually, really, I should thank you for that. Mamoulian ought to be remembered—not for being a cranky old has-been, but for having directed some classic pictures and classic stage musicals like, you know, Oklahoma! I knew him. Our minds matched. That there was some weird man-woman friction going on between us toward the end makes no difference. It fries me how little regard he gets nowadays, even in the film buff world.

But now my love, here’s the last item and I hope I can finish it before I have to go in to make dinner.

Okay. Here’s the connection between you and Mamoulian, and it has nothing to do with you as a musician. It has to do with that damn full dress of yours, which has aroused such a surprising fetish in me I’m exploring it in a special place.

Above John conducting his dream swing band in sweat-soaked silk shirt: The Allegro from Tchaikovsky’s 6th played by the RAM student orchestra conducted by the man I’ve fallen in love with.

Above John conducting his dream swing band in sweat-soaked silk shirt: The Allegro from Tchaikovsky’s 6th played by the RAM student orchestra conducted by the man I’ve fallen in love with.

*Actually, 5 that evening, but this is the first one was the one that made me want to find more things that featured you. The others: a fragment of you doing “Laura” in Birmingham; then with the JWO the MGM Overture in Leeds; the third was of you doing a bit of Vaughan Williams’s 2nd, again with the CBSO. The 5th was Friday Night Is Music Night from 2005. When you played Captain Kangaroo you made me completely yours.

Born Isaac Cozerbreit 8 May 1893 in London, died 7 September 1978, Findon Valley, Worthing, Charles Williams was one of Britain’s most prolific composers of light music, and was also responsible for numerous film scores. During his early career as a violinist he led for Sir Landon Ronald, Sir Thomas Beecham and Sir Edward Elgar. Like many of his contemporaries, he accompanied silent films, and became conductor of the New Gallery Cinema in London’s Regent Street. He worked on the first British all-sound film, Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail, from which followed many commissions as composer or conductor: The Thirty-Nine Steps (1935), Kipps (1941), The Night Has Eyes (1942), The Young Mr Pitt (1942), The Way To The Stars (1945; assisting Nicholas Brodszky, who is reported to have written only four notes of the main theme, leaving the rest to Williams), The Noose (1946), While I Live (1947) from which came his famous “Dream of Olwen“, and the American movie The Apartment (1960) which used Williams’s “Jealous Lover” originally heard in the British film The Romantic Age) as the title theme, reaching #1 in the US charts.

London publishers Chappell established their recorded music library in 1942, using Williams as composer and conductor of the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. These 78s made exclusively for radio, television, newsreel and film use, contain many pieces that were to become familiar as themes, such as “The Devil’s Galop” (signature tune of Dick Barton, Special Agent and here conducted in 2005 by my beloved John Wilson), “Girls In Grey” (BBC Television Newsreel), “High Adventure” (Friday Night Is Music Night) and “Majestic Fanfare” (Australian Television News). In his conducting capacity at Chappells he made the first recordings of works by several composers who were later to achieve fame in their own right, such as Robert Farnon, Sidney Torch, Clive Richardson and Peter Yorke.

An excerpt from my bonny John‘s comments:

Front Row: What’s so enthralling to you about the music of Erich Korngold?

John: It’s very much his own style… You hear two seconds of music and immediately you know it’s by Korngold because by the way he was 13 or 14 he had a fully developed late-Romantic Austro-German style and, you know, had it not been for the Nazis and the Second World War he would have continued to develop his operatic skills, his symphonic skills, and he would now be as established as Richard Strauss…

Above John, Andrew Haveron, John Mills, and other members of the Sinfonia of London: Front Row Interviews John Wilson at the top half.

Above John, Andrew Haveron, John Mills, and other members of the Sinfonia of London: Front Row Interviews John Wilson at the top half.

Front Row: What made you choose the particular pieces [for the Chandos recording] that you did?

John: I think the Symphony, Korngold’s Symphony in F-sharp, is the last great Austro-German romantic symphony and…it was written 1947 to 52, it took 5 years, and…I think it was the piece that Korngold spent, lavished the most time on. I think it was the piece that he felt was he felt he really had to write because it was a labor of love… And you know, he couldn’t get a satisfactory performance out of it during his lifetime because he was considered old hat…and in 1972 I think it was, it was discovered in the Munich orchestra’s library and the first recording performance given… And I just felt that the time had come for a revised sort of conception of this symphony of Korngold’s.

I Moderato

II Scherzo Allegro

III Adagio Lento

IV Allegro Finale

NOTES for Korngold: Symphony in F (Chandos, 2019) can be found here.